by Raoul Grifoni-Waterman, Copyright Policy Research Assistant at Authors Alliance, LL.M. Candidate at U.C. Berkeley Law, and Leiden University LL.M.

Every country leaves some room in its copyright laws to protect free expression and allow for the everyday uses of copyrighted works that creators and consumers need. But not everyone takes the same approach.

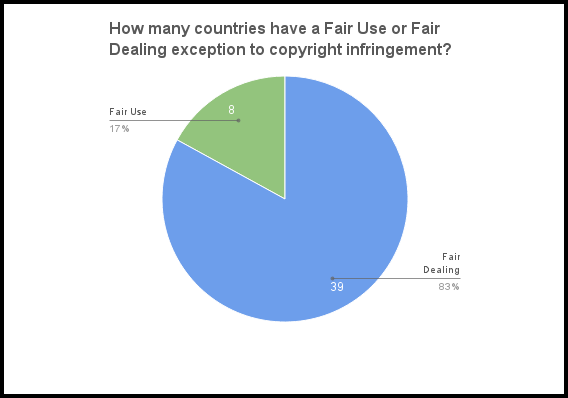

Out of 47 countries with fair use or fair dealing exceptions to copyright infringement, as surveyed in The Fair Use/Fair Dealing Handbook, only eight had a flexible fair use limitation on copyright infringement. The other type of surveyed exception is fair dealing, where an action must generally be directed toward a predetermined list of purposes in order to be deemed fair.

While the broader fair use exception—which Authors Alliance celebrates—is plainly the global outlier, there are indications that it is gaining traction.

The European Union, for example, provides an exhaustive list of copyright infringement exceptions in its 2001 Copyright Directive. However, while European Union member states may be constrained in implementing a general fair use exception in their national laws, there are calls for moving closer to its flexible approach. The United Kingdom, for example, was persuaded to examine fair use after hearing about its role in the U.S. technology economy. The resulting review found much commendable about fair use, and—conservatively—recommended the implementation of a new, more limited exception, to try and capture some of fair use’s openness to unexpected technological developments.

In January 2015, a member of the European Parliament’s Committee on Legal Affairs published a draft report on copyright reform. This report called for the adoption of “an open norm introducing flexibility in the interpretation of exceptions and limitations.” In July 2015, the European Parliament adopted a resolution based on the aforementioned draft report. A compromise was made in this resolution and the final text only urged the European Commission to construe new uses of content, made possible by technological developments, in line with preexisting exceptions and limitations. As the Electronic Frontier Foundation noted, this is nowhere near to the U.S. fair use exception, but it is movement toward it.

The European Commission (the European Union’s executive body) then went on to release a communication about the new European copyright framework at the end of 2015. None of the legislative proposals that the European Commission will consider by the spring of 2016 take the European Parliament’s recommendation into account. The main focus of the new framework is “to increase the level of harmonisation, make relevant exceptions mandatory for Member States to implement and ensure that they function across borders within the EU.”

Something similar happened in Australia, where the Australian Law Reform Commission suggested that “Australia is ready for, and needs, a fair use exception now.” Australia’s attorney general was not convinced by the report, however, and as of March 2015, Australia still has not implemented a fair use exception.

Meanwhile in Canada, the courts have found room for more flexibility within that country’s existing fair dealing statute, moving it the law substantially closer to a fair use model without abandoning the fair dealing framework.

It would be shortsighted to look only at the current state of affairs as depicted in the survey on fair use/fair dealing exceptions. As noted here, recently there have been attempts to implement a fair use exception in the United Kingdom, the European Union and Australia. Even though these initiatives did not result in the implementation of new fair use exceptions, they show a willingness by members of parliament and law reform commissions alike to implement these exceptions. Fair use, which serves authors, creators, students, educators, and the public good, might just be going global in the future.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.