We would like to thank Authors Alliance legal research assistant Allison Davenport for writing the following analysis.

Two courts in the Southern District of New York recently decided two fair use cases that, on the surface, may appear to be similar but ultimately reached different outcomes. In one, a beloved children’s classic is grown-up for an adults-only stage adaptation. In another, classic adult novels are presented as colorfully illustrated children’s books. Yet, the former was judged to be a fair use and the latter was not. What led the court to these opposite rulings, and what can it teach us about how fair use works?

Fair Use

Fair use is a limitation on U.S. Copyright law which allows authors to use portions of a copyrighted work without permission or payment, so long as that use is “fair.” Courts consider at least four factors when determining whether a use is fair: 1) the purpose and character of the challenged use (often asking if the use is “transformative”), 2) the nature of the copyrighted work, 3) the amount and substantiality of the copyrighted work used, and 4) the effect on the potential market for the copyrighted work. These four factors do not work in isolation and must be carefully weighed together to determine if a work is fair.

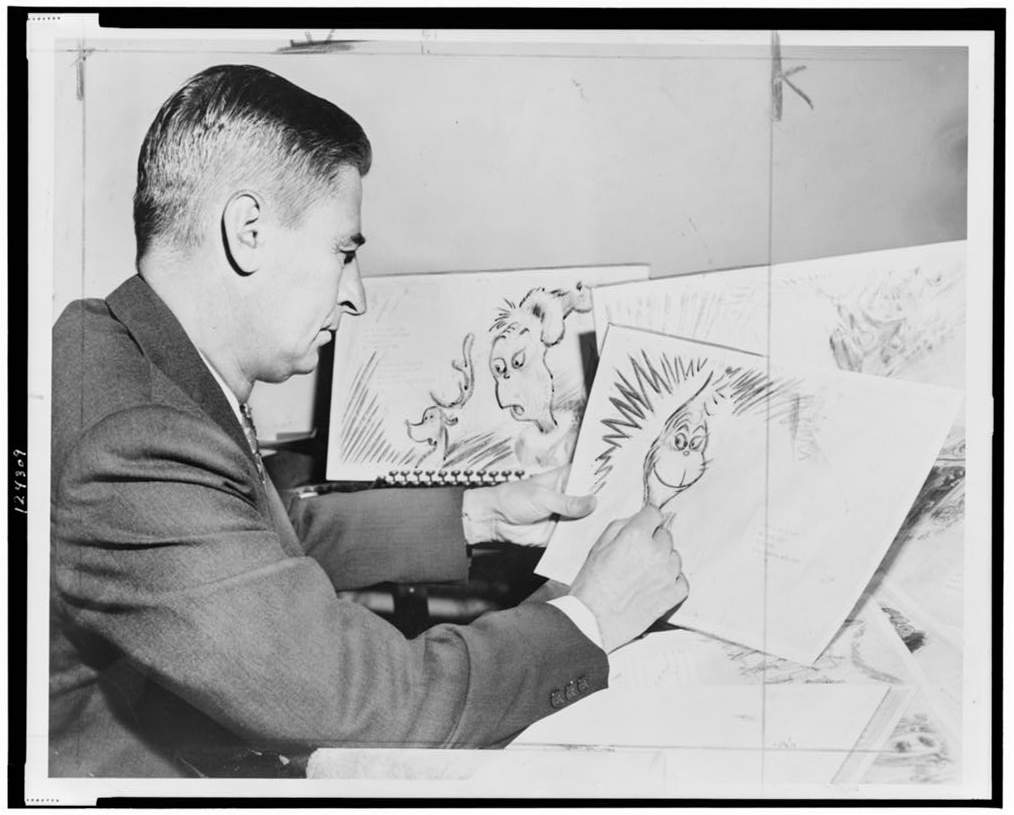

Who’s Holiday! – Matthew Lombardo and Who’s Holiday, LLC v. Dr. Seuss Enterprises

“In creating these juxtapositions, the Play, rather than trading on the character of Cindy-Lou Who and the setting of Who-Ville for commercial gain, turns these Seussian staples upside down and makes their saccharin qualities objects of ridicule.”

Who’s Holiday! is a one-woman stage play by Matthew Lombardo which features a 45-year-old Cindy-Lou Who from How the Grinch Stole Christmas recounting the circumstances that led to her life as a drug addict living in a trailer, alone on Christmas. In the play, Cindy retells the events of Seuss’ story but then goes on to describe how she became pregnant with the Grinch’s baby at 18, married him, and suffered through unemployment and starvation before eventually killing the Grinch and being imprisoned for his murder. The play is told in rhyming couplets similar to the style of Seuss’ original, with a few exceptions.

The district court found that Lombardo’s use of the characters and settings from How the Grinch Stole Christmas was a fair use largely because the work was a parody of Seuss’ original. Whether or not a work is a parody falls under the first factor of fair use. If a work is judged to be a parody, it has an “obvious claim to transformative value” because it has a different expression, meaning, and message than the original. The court characterized Who’s Holiday! as a parody because it used the characters, settings, and style from How the Grinch Stole Christmas in an exaggerated way to criticize the original and make it appear ridiculous. Specifically, the court found that the vulgar and distressing subject matter of the play here was intended to contradict the utopian society depicted in the children’s book.

When a work is a parody, the remaining three factors are unlikely to tip the balance against fair use. Although How the Grinch Stole Christmas is a creative work and, as such, the court found that factor two weighed against fair use, this factor is weighed less heavily in parody cases. Under the third factor, because parodies must use enough of a work for audiences to recognize the original, the court found that the amount used was reasonable in light of the purpose. The court also found that the fourth factor weighed toward fair use because there was “virtually no possibility that consumers will go see the play in lieu of reading Grinch or watching an authorized derivative work, such as the 2000 film Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas. . .” and thus Lombardo’s work did not supplant the market for the original or any derivatives that Dr. Seuss Enterprises would be likely to license.

KinderGuides – Penguin Random House, et. al. v. Moppet Books

“Fair use, however, is not a jacket to be worn over an otherwise infringing outfit. One cannot add a bit of commentary to convert an unauthorized derivative work into a protectable publication.”

KinderGuides, by Fredrik Colting (who previously claimed fair use in a case involving The Catcher in the Rye) and Melissa Medina, retell classic novels in the form of illustrated children’s books. The aim of these books was to make adult novels accessible to children by making the books shorter and removing adult themes and language. Four books were published before the lawsuit was filed (On the Road, The Old Man and the Sea, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and 2001: A Space Odyssey), and KinderGuides planned to release a total of 50 retellings of classic novels.

Once again, the most important factor in this case was the first. KinderGuides argued that their works are transformative because they shortened the books, took out adult-oriented material, and included study guides in the back of each book. The court, however, found that these changes were not enough because the KinderGuides “seek to fairly represent the original” with no new “insights or understandings.” Because KinderGuides tried to stay as faithful to the originals as possible, the few additions of study questions at the end were not enough to make their use transformative. Additionally, the fictional character of the original works led the court to find that the second factor weighed against fair use. The court also determined the third factor weighed against fair use because the majority of the KinderGuides content was devoted to retelling the original stories rather than analysis (there were about two pages of study guide for a book of several dozen pages). Finally, the court found that the fourth factor of fair use weighed against KinderGuides because it was usurping the existing potential market for children’s books based on classic novels.

What can we learn from this?

These two decisions turn on the transformative qualities of the works claiming fair use. While there are many other ways a work may be considered transformative, parody and criticism are almost always considered transformative. For works claiming to be a parody, a good rule of thumb is to ask whether the new work needed to use the original to make its point or if any copyrighted work would have sufficed to fill the space. Here, Who’s Holiday! would not have been able to achieve the same effect (the juxtaposition of the harsh realities of life with Seuss’ utopian vision of Who-Ville) without making reference to the original work through the use of its characters and rhyme scheme. KinderGuides, however, could have used any number of underlying classics in their children’s books, and in fact planned to do just that.

For critical works, fair use generally allows the new work to use an amount of the original reasonably necessary to support the arguments or analysis. For example, using stills from a film in a review or using quotes from a novel in an academic paper would likely be considered fair use. Where Who’s Holiday! used small details from the original such as character names, places, and rhyming style in order to criticize the naiveté of How the Grinch Stole Christmas, KinderGuides faithfully retold the entire stories of the original novels with only a short, poorly integrated analysis at the end of the book. The criticism in Who’s Holiday! was pervasive, and in KinderGuides, it felt more like an afterthought (in fact, the authors of KinderGuides admitted to the court that they added these study guides so they could later claim fair use).

Another important takeaway from these cases is the way the fourth factor is interpreted. Part of the justification for the fair use doctrine is that it creates an outlet for works which would not normally be licensed by the original creator, such as criticism or parody. An author’s refusal to license derivative works is not enough to justify fair use, however. The use must be one where the type of derivative work being made does not fall into “traditional, reasonable, or likely to be developed markets.” For example, while an author may want to license their work in traditional derivative markets such as film and television, it is unlikely they will ever license it for a blistering criticism or parody which makes fun of the original work. Thus, the difference between children’s versions of adult classics and a play which introduces themes such as drug abuse and murder into a children’s book is that the former takes advantage of a fairly traditional and widespread derivative market that authors would likely wish to exploit for themselves, while the latter is unlikely to ever be officially authorized by the copyright owner of an original work.

Fair use decisions may seem complicated, but looking at real cases and using best practices guides are excellent ways for authors to navigate the legal landscape of fair use. Authors Alliance has a long history of advocating for a robust interpretation of fair use, filing amici curiae briefs in both the Google Books and Cambridge University Press cases, in which we argued that making fair use of works in these cases helps authors keep their works discoverable and in the hands of readers. We also offer resources to authors who wish to learn more about fair use on our Fair Use Resource Page, and we are in the process of developing our own fair use best practices guide for non-fiction authors.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.