We’d like to thank co-authors Kyle K. Courtney and David R. Hansen for permission to re-post the following article, which originally appeared on the Copyright at Harvard Library blog on March 1, 2019.

One of the beautiful things about fair use is how it can soften the copyright act, which is in many ways highly structured and rigid, to provide flexibility for new, innovative technology.

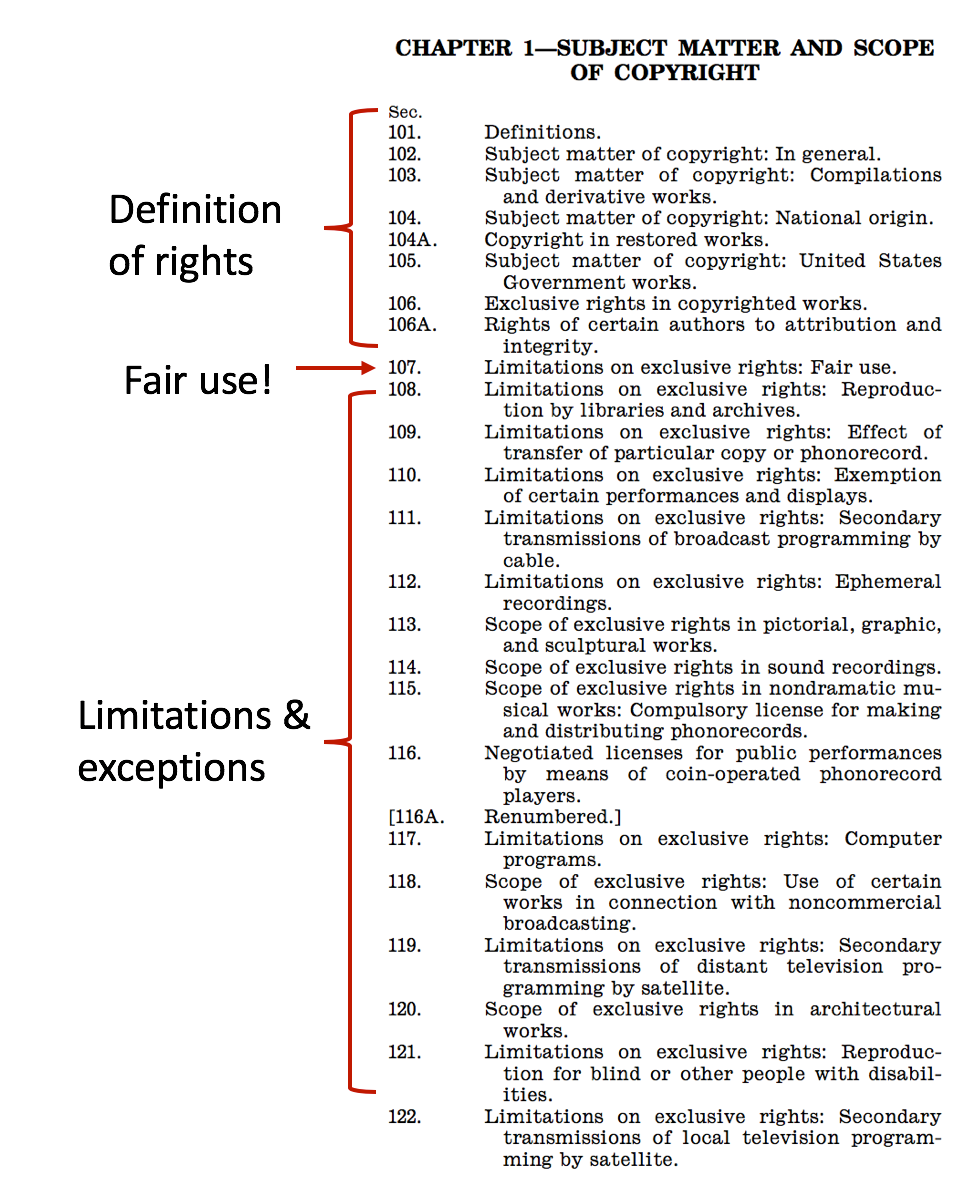

To understand how, it’s worth appreciating the structure of the Copyright Act. If you look at the table of contents of Chapter 1 of the Act (“Subject Matter and Scope of Copyright”), you see the first several sections define basic terms such as copyrightable subject matter. Included in that first half of the chapter is Section 106, which defines the exclusive rights held by rights holders: the right to control copying, the creation of derivative works, public distribution, public performance, and display. In the bottom half of the Act, Sections 108 to 122 provide for a wide variety of limitations and exceptions to those owners’ exclusive rights. These exceptions are largely for the benefit of users and the public, including specific exceptions to help libraries, teachers, blind and print-disabled users, non-commercial broadcast TV stations, and so on.

Then, there’s fair use. As if perfectly positioned to balance between the broad set of rights granted to owners and the specific limitations for the benefit of users and the public, “fair use” is codified in Section 107, though it really isn’t a creature of statute. Fair use is a doctrine, developed by courts as an “equitable rule of reason” that requires courts to “avoid rigid application of the Copyright Statute when on occasion it would stifle the very creativity which that law was designed to foster.” In that role, fair use has facilitated all sorts of technological innovations that Congress never could have anticipated, allowing copyrighted works and new technology to work together in harmony.

One particularly innovative system developed to enhance access to works is “controlled digital lending” (“CDL”):

CDL enables a library to circulate a digitized title in place of a physical one in a controlled manner. Under this approach, a library may only loan simultaneously the number of copies that it has legitimately acquired, usually through purchase or donation….[I]t could only circulate the same number of copies that it owned before digitization. Essentially, CDL must maintain an “owned to loaned” ratio. Circulation in any format is controlled so that only one user can use any given copy at a time, for a limited time. Further, CDL systems generally employ appropriate technical measures to prevent users from retaining a permanent copy or distributing additional copies.

While the courts have yet to weigh in directly on the CDL concept, we now have some guidance from a case in the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, Capitol Records, LLC v. ReDigi Inc. This case is about the development of an online marketplace created by ReDigi, which facilitated the sale of “used” mp3 music files. Capitol Records sued ReDigi, alleging that ReDigi infringed its exclusive rights to reproduction and distribution when it attempted to use a particular transfer method to sell the used mp3s.

The Court of Appeals upheld a lower court ruling that the doctrine of first sale is only an exception to the public distribution right and, therefore, does not protect digital lending because, in that process, new copies of a work are always made.

The court also rejected ReDigi’s fair use assertion. It found that the use was commercial in nature, was considered non-transformative, and replicated works exactly and precisely; simply put, they created mirror image copies of existing digital files. Further, though the libraries associations in their briefs had raised the issue of a nexus of connection between fair use and specific copyright exceptions, such as Section 109 and 108, as an extension of Congressional policy that should influence the fair use analysis, the court did not discuss that argument.

That the court ruled ReDigi, a commercial enterprise, had interfered with the market for iTunes-licensed mp3s and their effort was not a transformative fair use, comes as no surprise to most lawyers and copyright scholars.

However, the decision, written by the creator of the modern transformative fair use doctrine, Judge Pierre Laval, contains several important lessons for CDL.

Transformative Use

First, the case raises a significant question as to whether CDL of digitized books may be “transformative” in nature. In the decision, examining the first factor, Judge Leval explains that a use can be transformative when it “utilizes technology to achieve the transformative purpose of improving delivery of content without unreasonably encroaching on the commercial entitlements of the rights holder.” For physical books, especially those that are difficult to obtain, this application of “transformative use” has a direct correlation to the core application of CDL.

Further, this quote interprets another critical technology and fair use case from the U.S. Supreme Court, Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417 (1984), famously called the “Betamax case.” Since its decision in 1984, the Sony ruling helped establish and foster the creation of new and vital technology, from personal computers and iPods to sampling machines and TiVo. This Sony quote was most recently used in another Second Circuit case, Fox News Network, LLC v. TVEyes, where the same court laid out this particular reading of Sony. So, ReDigi here is drawing upon the precedent of two important transformative fair use cases to make its point. Under this transformative use definition, CDL should be determined to be transformative by the courts, especially if the commercial rights of the rights holder are not unreasonably encroached.

Therefore, while the court found ReDigi’s use to not be transformative, the Second Circuit opened the door for continued technological development, especially for non-commercial transformative uses under the first factor, like CDL. In fact, according to several scholars (Michelle Wu, Kevin Smith, Aaron Perzanowski), this creates a much stronger argument that CDL would be ruled a transformative fair use by a court.

Market Harm

The Second Circuit held that the ReDigi system caused market harm under the fourth factor of the fair use statute. Again, this is not a surprise to the copyright world. The court found that the service provider had no actual control of the objects being sold and that it “made reproductions of Plaintiffs’ works for the purpose of resale in competition with the Plaintiffs’ market for the sale of their sound recordings.”

What does this mean for CDL’s analysis under the fourth factor? Here, again, based on the language of the ReDigi decision, CDL looks pretty different. The ReDigi resales were exact, bit-for-bit replicas of the original sold in direct competition with “new” mp3s online through other marketplaces, such as iTunes. The substitutionary effect was clear, especially since the mp3 format is the operative market experiencing harm. For digitized copies of print books used for CDL, the substitutionary effect is far less clear. With most 20th-century books—the books that we feel are the best candidates for CDL—the market to date has been exclusively print. For those books, some new evidence from the Google Books digitization project suggests that digitization may in fact act as a complementary good, allowing digital discovery to encourage new interest in long-neglected works.

CDL doesn’t compete with a recognized market. When a library legally acquires an item, it has the right, under the first sale doctrine, to continue to use that work unimpeded by any further permission or fees of the copyright holder. CDL’s digitized copy replaces the legitimately acquired copy, not an unpurchased copy in the marketplace. To the extent there is a “market harm,” it’s one that is already built into the transaction and built into copyright law: libraries are already legally permitted to circulate and loan their materials. The CDL “own-to-loan ratio” ensures that the market harm for the digital is the exact same as circulating the original item.

Again, the language of the ReDigi court should be examined closely. The court distinguishes substitutionary markets from those that are complementary and natural extensions of the use inherent with purchasing the original: “to the extent a reproduction was made solely for cloud storage of the user’s music on ReDigi’s server, and not to facilitate resale, the reproduction would likely be fair use just as the copying at issue in Sony was fair use.” Reading this language through the lens of CDL, a modern reproduction service, such as CDL, that further enhances the owner’s use of materials that were purchased under first sale or owned under other authorized means would also qualify as a fair use.

All in all, the ReDigi case most certainly does not settle the CDL issue; if anything, the specific language of the court emphasizes the potential for more non-commercial transformative uses like CDL.

David Hansen is the Associate University Librarian for Research, Collections & Scholarly Communications at Duke University Libraries. Before coming to Duke he was a Clinical Assistant Professor and Faculty Research Librarian at UNC School of Law. And before that, he was a fellow at UC Berkeley Law in its Digital Library Copyright Project.

Kyle K. Courtney is Copyright Advisor and Program Manager at Harvard Library’s Office for Scholarly Communication (OSC). Before joining the OSC, Kyle managed the Faculty Research And Scholarly Support Services department at Harvard Law School Library.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.