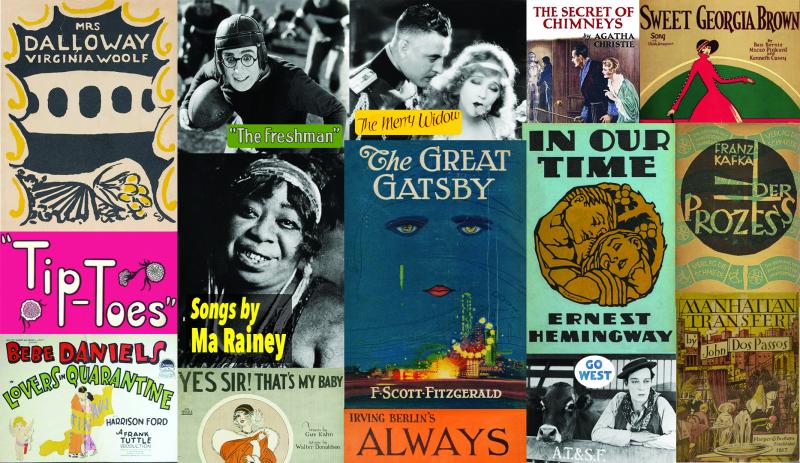

Last week, we celebrated a new batch of works from 1925 entering the public domain. In copyright, the public domain is the commons of material that is not protected by copyright. When a work enters the public domain, anyone may do anything they want with the work, including activities that were formerly the “exclusive right” of the copyright holder like making copies of, sharing, and adapting the work.

Some people mistakenly think that the “public domain” means anything that is publicly available. This is wrong: The public domain has nothing to do with what is readily available for public consumption. Just because a work is freely available on the internet, for example, doesn’t mean the work is in the public domain. Under today’s copyright laws, copyright protection is automatic. This means, for example, that a photographer could take and upload a photograph to a publicly accessible website, and—despite its public availability online—unauthorized uses of the photograph may be infringing, unless the use is otherwise allowed under an exception to copyright.

Just how do works become a part of the public domain? In this post, we’ll share some of the ways in which works enter the public domain or simply exist as a part of the public domain because of the limits of copyright.

Copyright Expiration

One way that works become a part of the public domain is the expiration of their copyright protection. Copyright protects works for a limited time and after that, the copyright expires and works fall into the public domain. Under U.S. copyright law, as of 2021, all works first published in the United States in 1925 or earlier are now in the public domain due to copyright expiration. Copyright law has changed over time and the term of copyright is now calculated based on the life of the author. Under today’s copyright laws, works created by an individual author today won’t enter the public domain until 70 years after the author’s death.

It can be devilishly difficult to determine whether a work’s copyright has expired. For example, while works first published in the United States in 1925 or earlier are in the public domain, unpublished works created prior to 1925 may not be. We recommend Peter Hirtle’s Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States and Berkeley Law’s “Is it in the Public Domain?” Handbook to help you evaluate a work’s copyright status.

Failure to Comply With Formalities

While 2021 brings certainty that works first published in the United States in 1925 are in the public domain, changes in copyright duration and renewal requirements during the 20th century mean that works first published in the United States between 1926 and March 1, 1989 could also be in the public domain because their copyrights were not renewed or because the copyright owner failed to comply with other “formalities” that used to be required for copyright protection. These formalities included requirements that the copyright owner register her work with the Copyright Office and mark the work with a copyright notice upon publication. Analysis from the New York Public Library revealed that approximately 75% of copyrights for books were not renewed between 1923-1964, meaning roughly 480,000 books from this period are most likely in the public domain.

Under today’s copyright laws, authors of new published works are no longer required to comply with any formalities to be eligible for copyright protection, though there are significant benefits to doing so.

Uncopyrightable Subject Matter

Copyright law is not unlimited. There are certain things that are seen as fundamental building blocks of creativity and authorship and are therefore simply not protected by copyright, entering the public domain automatically.

An important category of things that are not copyrightable are facts—even if those facts are obscure or were difficult to collect. For instance, suppose that a historian spent several years reviewing field reports and compiling an exact, day-by-day chronology of military actions during the Vietnam War. Even though the historian expended significant time and resources to create this chronology, the facts themselves would be free for anyone to use. That said, the way that the facts are expressed—such as how they are articulated in an article or a book—is copyrightable. The lack of copyright protection for facts is central to copyright law: Even “asserted truths,” or information presented as factual which later turns out to be untrue, are part of the public domain.

Ideas, themes, and scènes à faire are categories of expression that are also outside of copyright protection. These concepts are closely related, and the overarching justification for excluding them from copyright protection is that they are simply too general and standard to a particular genre or convention for an individual creator to be granted a temporary monopoly on them. Here again, though copying the words used to express the idea or theme could constitute infringement, the similarity of general ideas, themes, or other elements of a work which are standard in the treatment of a given topic cannot form the basis of an infringement claim. For more on ideas, themes, and scènes à faire, check out our post on uncopyrightable subject matter for fiction writers.

Other Exclusions

The U.S. Copyright Office provides information about additional types of works and subject matter that do not qualify for copyright protection, including names, titles, and short phrases; typeface, fonts, and lettering; blank forms; and familiar symbols and designs. It is worth noting that other areas of intellectual property, such as patent or trademark law, could provide protection for categories that are not eligible for copyright protection.

The Copyright Act provides that works created by the United States federal government are never eligible for copyright protection, though this rule does not apply to works created by U.S. state governments or foreign governments. And under the government edicts doctrine, judicial opinions, administrative rulings, legislative enactments, public ordinances, and similar official legal documents are not copyrightable for reasons of public policy.

The U.S. Copyright Office also reminds potential registrants that works that “lack human authorship” are uncopyrightable, using as an example “a photograph taken by a monkey.” Sound familiar?

Abandonment / No Rights Reserved

In theory, a copyright owner can voluntarily abandon her copyright prior to the expiration of the work’s copyright term by engaging in an overt act reflecting the intent to relinquish her rights. Abandoned works then become part of the public domain, free from copyright and available for anyone to use.

Creative Commons offers a “No Rights Reserved” tool for copyright owners who wish to waive copyright interests in their works and thereby place them as completely as possible in the public domain. And recently, satirist Tom Lehrer added a statement to his website granting permission to the public to download and reuse his lyrics, noting that they “should be treated as though they were in the public domain.” That said, a scholarly article by Dave Fagundes and Aaron Perzanowski criticizes the current state of the law surrounding copyright abandonment. The authors assert that the lack of a clear, reliable way to abandon copyright frustrates authors who wish to abandon their copyrights, and the practical effectiveness of abandonment is undermined by the lack of a broadly accessible record of abandoned works.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.