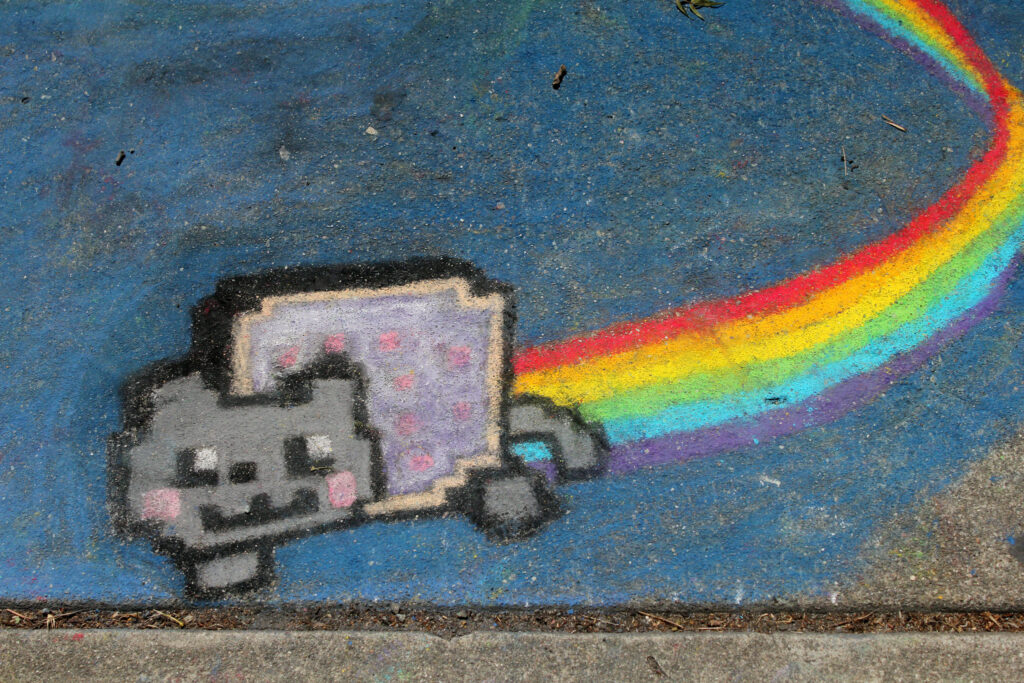

News about non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) selling for eye-popping sums has been hard to miss. Nyan Cat, an iconic GIF of a cat with a Pop-Tart for a torso flying through space, sold for nearly $600,000. Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey’s first tweet—a mere five words—recently sold for nearly $3,000,000. And an NFT representing digital artist Beeple’s Everydays: the First 5000 Days collage set a record in March as the third most expensive artwork ever sold from a living artist when it sold at a Christie’s auction for more than $69,000,000.

While NFTs offer a new avenue for creators to get paid for digital assets, many have questions about what exactly an NFT holder “owns” in relation to the digital object and whether that ownership includes copyrights. This post explains these concepts and how they relate to ownership of physical objects.

NFTs are unique cryptographic assets that exist on a blockchain. NFTs facilitate the sale of digital items by providing owners of digital objects with a registration record to keep track of and verify the ownership of a digital file. Because NFTs can be used to represent unique digital items, they provide a way for individuals to own and collect “authentic” versions of digitally native assets.

Digital artists have struggled to monetize their creations since digital art can be readily copied and shared online in its original form. NFTs don’t change this: digital files represented by NFTs can still be copied and shared (setting aside the copyright implications of doing so). Instead, NFTs represent something that cannot be copied: the right to claim ownership of the underlying digital work. In this respect, NFTs can be used to create artificial scarcity by making only one NFT to represent a work, bringing “ownership” of a digital work of art more in line with ownership of a physical work of art.

Like physical art, the NFT itself can be sold. Because of the record keeping function of the blockchain, some NFTs ensure that artists get a percentage of the sales proceeds every time the ownership changes hands on the secondary market, a feature that is somewhat akin to an artist resale right, or droit de suite, that exists in many European countries and provides that artists receive royalties for their works when they are resold.

On its own, an NFT does not transfer intellectual property rights to the NFT holder. This means without an additional license or transfer of copyrights, the NFT holder does not acquire the rights to make and sell copies of the digital artwork. While this may seem surprising, this is analogous to how ownership works in the physical world: the ownership of a physical object is distinct from the ownership of copyright. The owner of a painting may do whatever she wants with the physical copy—sell it, give it away, etc.—but she does not acquire the copyrights in the painting simply by purchasing the physical copy. Without further authorization, the owner of a copyrighted painting typically cannot, for example, make and sell greeting cards with copies of the painting on them, which would be unauthorized reproductions of the work. In this way, ownership of the NFT is similar to owning a physical copy of any creative work, though the NFT owner simply has the token recording ownership rather than a physical manifestation of the object.

That said, a digital artist can elect to transfer or license some or all or of her copyrights to the NFT holder. For example, when MetaKoven bought the NFT representing Beeple’s Everydays at auction, he also acquired some rights to display the artwork online. While it is not yet clear what MetaKoven will do with these rights with respect to Everydays, in December he purchased a different collection of digital artworks by Beeple, which he is displaying in a digital museum (where he is also selling fractionalized ownership of the collection). Whether art lovers will find the virtual gallery experience approachable, let alone a satisfactory parallel to the analog world—and whether collectors and investors will continue to find appeal in ownership of NFTs—is yet to be seen.

Authors of written works wondering what opportunities they might have to take advantage of the NFT craze may look longingly at the recent sale of a New York Times column by Kevin Roose about NFTs that was itself turned into an NFT. Pitched as “the first article in the almost 170-year history of The Times to be distributed as an NFT,” it recently sold for $560,000 in a charity auction. Illustrating the concept that ownership of the NFT does not itself transfer any copyrights, Roose’s article makes clear “the NFT does not include the copyright to the article or any reproduction or syndication rights.” The NFT holder acquires no more rights to copy and share the article than someone who accesses the column through their New York Times digital subscription or who has a copy of the Times delivered each morning.

Unsurprisingly, commentators disagree as to whether the NFT hype is here to stay or will soon die down. In the meantime, NFTs offer a novel way for tech savvy creators to bring attention to and potentially monetize their digital works.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.