Our last post highlighted one of the amicus briefs filed in the Hachette v. Internet Archive lawsuit, which made the point that controlled digital lending serves important privacy interests for library readers. Today I want to highlight a second new issue introduced on appeal and addressed by almost every amici: the proper way to assess whether a given use is “non-commercial.”

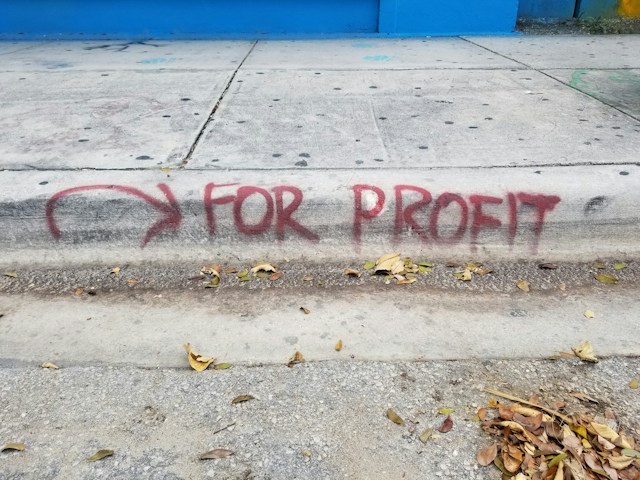

“Non-commercial” use is important because the first fair use factor directs courts to assess “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes.” Before the district court, neither Internet Archive (IA) nor amici who filed in support of IA paid considerable attention to arguing about whether IA’s use was commercial, I think because it seemed so clear that lending books for free to library patrons appeared to us a paradigmatic example of non-commercial use. It came as a shock, therefore, when the District Court in this case concluded that “IA stands to profit” from its use and that the use was therefore commercial.

The Court’s reasoning was odd. While it recognized that IA “is a non-profit organization that does not charge patrons to borrow books and because private reading is noncommercial in nature,” the court concluded that because IA gains “an advantage or benefit from its distribution and use” of the works at issue, its use was commercial. Among the “benefits” that the court listed:

- IA exploits the Works in Suit without paying the customary price

- IA uses its Website to attract new members, solicit donations, and bolster its standing in the library community.

- Better World Books also pays IA whenever a patron buys a used book from BWB after clicking on the “Purchase at Better World Books” button that appears on the top of webpages for ebooks on the Website.

Although almost every amici addressed the problems with this approach to “non-commercial” use, three briefs, in particular, added important additional context, explaining both why the district court was wrong on the law and why its rule would have dramatically negative implications for other libraries and nonprofit organizations.

First, the Association of Research Libraries and the American Library Association, represented by Brandon Butler, make a forceful legal argument in their amicus brief about why the district court’s baseline formulation of commerciality (benefit without paying the customary price) was wrong:

The district court’s determination that the Internet Archive (“IA”) was engaged in a “commercial” use for purposes of the first statutory factor is based on a circular argument that seemingly renders every would-be fair use “commercial” so long as the user benefits in some way from their use. This cannot be the law, and in the Second Circuit it is not. The correct standard is clearly stated in American Geophysical Union v. Texaco Inc., 60 F. 3d 913 (2d Cir. 1994), a case the district court ignored entirely.

ARL and ALA then go on to highlight numerous examples of appellate courts (including the Second Circuit) rejecting this approach such as in the 11th Circuit in the Georgia State E-reserves copyright lawsuit: “Of course, any unlicensed use of copyrighted material profits the user in the sense that the user does not pay a potential licensing fee, allowing the user to keep his or her money. If this analysis were persuasive, no use could qualify as ’nonprofit’ under the first factor.”

Second was an amicus brief by law professor Rebecca Tushnet on behalf of Intellectual Property Law Scholars, explaining both whycopyright law and fair use favor non-commercial uses, and how IA’s uses fall squarely within the public-benefit objectives of the law. The brief begins by highlighting the close connection between non-commercial use and the goals of copyright:

The constitutional goal of copyright protection is to “promote the progress of science and useful arts,” Art. I, sec. 1, cl. 8, and the first copyright law was “an act for the encouragement of learning,” Cambridge University Press v. Patton, 769 F.3d 1232, 1256 (11th Cir. 2014). This case provides an opportunity for this Court to reaffirm that vision by recognizing the special role that noncommercial, nonprofit uses play in supporting freedom of speech and access to knowledge.

The IP Professors Brief then goes on to highlight the many ways that Congress has indicated that library lending should be treated favorably because it furthers objectives of supporting learning, and how the court’s constrained reading of “non-commercial” is actually in conflict with how that term is used elsewhere in the Copyright Act (for example, Sections 111, 114, and 118 for non-commercial broadcasters, or Section 1008 for non-commercial consumers who copy music). The brief then goes on to make a strong case for why the district court wasn’t only mistaken, but that library lending should presumptively be treated as non-commercial.

Finally, we see the amicus brief from the Wikimedia Foundation, Creative Commons, and Project Gutenberg, represented by Jef Pearlman and a team of students at the USC IP & Technology Law Clinic. Their brief highlighted in detail the practical challenges that the district court’s approach to non-commercial use would pose for all sorts of online nonprofits. The brief explains how nonprofits that raise money will inevitably include donation buttons on pages with fair use content, rely on volunteer contributions, and engage in revenue-generated activities to support their work, which in some cases require millions of dollars for technical infrastructure. The brief explains:

The district court defined “commercial” under the first fair use factor far too broadly, inextricably linking secondary uses to fundraising even when those activities are, in practice, completely unrelated. In evaluating what constitutes commercial use, the district court misapplied several considerations and ignored other critical considerations. As a result, the district court’s ruling threatens nonprofit organizations who make fair use of copyrighted works. Adopting the district court’s approach would threaten both the processes of nonprofit fundraising and the methods by which educational nonprofits provide their services.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.