In the course of our work on Federal public access policies and the Nelson Memo, one of the objections I’ve encountered recently is that federal agency initiatives to provide immediate public access to scholarly articles run afoul of the Bayh-Dole Act or may imperil a university’s patent rights to inventions created pursuant to federal funding. Another related objection is that Stanford v. Roche, a case about how a university must go about securing rights in patentable inventions from their faculty under Bayh-Dole, affects how universities obtain sufficient rights to comply with federal public access policies.

I thought it would be worth explaining why we don’t think these are realistic problems for federal public access law or policy.

Bayh-Dole does not affect copyright in scholarly articles

The Bayh-Dole Act is an amendment to U.S. patent law passed in 1980 that gives nonprofits and small businesses the right to retain patent rights in inventions developed using federal funding. Before Bayh-Dole, federal grant recipients were required by some federal agencies’ policies to assign patent rights arising from federally funded research to the government. To encourage institutions receiving federal research funding to commercialize inventions for public benefit, Bayh-Dole instead allowed institutions receiving federal grants the right to retain rights to an invention. If a grantee elects to retain title to an invention (rather than commercializing it), they must grant the government a nonexclusive, nontransferable, irrevocable, paid-up license to use the invention. Unreasonable refusal to develop or commercialize may result in the government exercising “march-in” rights to license the invention to others (one of the more controversial parts of the legislation).

The rights that Bayh-Dole secures for government contractors and grantees apply to “subject inventions.” “Inventions” it defines as “any invention or discovery which is or may be patentable or otherwise protectable under [US patent laws], or any novel variety of plant which is or may be protectable under the Plant Variety Protection Act. . . . .” In turn, “subject inventions” are “any invention of the contractor conceived or first actually reduced to practice in the performance of work under a funding agreement.” In other words, “subject inventions” are inventions that were developed within the scope of a Federal grant.

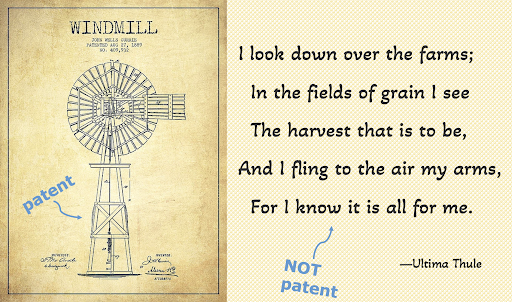

The Nelson Memo also applies to grant outputs, but not inventions; it applies to “peer-reviewed scholarly publications.” Peer-reviewed scholarly publications, of course, are not inventions nor would any rights under patent law apply to them. Scholarly publications are creative works of authorship, reuse of which is governed by copyright law under Title 17 of the United States Code, not covered by Bayh-Dole. It is true that copyrights and patents are sometimes discussed together as “intellectual property,” and courts sometimes even borrow concepts from one body of law to the other. But for the most part, different statutes and different cases govern how rights under each may be created, owned, licensed, and used.

Federal regulations about agency ownership and licensing of patent and copyright rights reflect that they are different. As discussed at length in this paper we published a few months ago (or see the one-page summary), grant-making agencies have for nearly half a century reserved certain rights in copyrighted grant outputs under a provision known as the “Federal Purpose License.” That license, which is codified in 2 C.F.R. § 200.315(b), provides that:

“To the extent permitted by law, the recipient or subrecipient may copyright any work that is subject to copyright and was developed, or for which ownership was acquired, under a Federal award. The Federal agency reserves a royalty-free, nonexclusive, and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use the work for Federal purposes and to authorize others to do so. This includes the right to require recipients and subrecipients to make such works available through agency-designated public access repositories.” (emphasis added).

Note that the Federal Purpose License is limited to copyrightable works. By contrast, in the very next sub-section of the regulation, we see that rights in patents are treated differently:

“[T]he recipient or subrecipient is subject to applicable regulations governing patents and inventions, including government-wide regulations in 37 CFR part 401 [the implementing regulations for Bayh-Dole].” 2 C.F.R. § 200.315(c)(emphasis added).

It is, of course, possible that in the course of federally funded research, one might produce both a patentable invention that is subject to Bayh-Dole and a copyrighted research article on the same subject. But this does not make Bayh-Dole applicable to the copyright rights in the article, nor does it mean that the Federal Purpose License (a copyright license) affects patent rights under Bayh-Dole regulations. The copyright provisions cover copyrightable works; the patent provisions the patents.

Disclosure of Inventions or Discoveries

If you’ve worked with your campus technology transfer office before, you know that public disclosure of new research (e.g., in a research article) can be a problem if one hopes to obtain a patent for an invention discussed in that publication. U.S. patent law rewards new and non-obvious inventions, and so the law provides in 35 U.S.C. § 102(a) that one is not entitled to a patent if “the claimed invention was patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention.”

Note that the statute specifically calls out description of the invention “in a print publication.” Prior print publication turns on “public accessibility,” which the courts have explained as being “disseminated or otherwise made available to the extent that persons interested and ordinarily skilled in the subject matter or art exercising reasonable diligence[ ] can locate it.” And so, the standard is far less than the “worldwide free public access” provided by the public access databases under the Nelson memo. For example, the Federal Circuit has found that a dissertation shelved and indexed in a card catalog at a German University qualified as publicly accessible. The court has also concluded that an oral presentation of a paper (with dissemination of the paper itself to only six people) at a conference satisfied the test. Similarly, the Federal Circuit has held that electronic distribution via a subscription email list qualified as publicly accessible. The point is that if you’ve already published a paper in a peer-reviewed journal that sufficiently describes the invention–even if just published via a subscription route and not available for free–you have almost certainly already disclosed the invention. Further expanding the reach through a public access repository would make no difference.

Public access policies implementing the Nelson Memo do not compel researchers or universities to disclose inventions prematurely, thus having no impact on patentability. It merely states that once you choose to publish your research in an article, it must be promptly accessible to the public for free, no later than the publication date, in a public access repository. Whether the article is restricted to subscribers only or made openly available does not affect its status as a public disclosure for patent purposes.

Stanford v. Roche

Stanford v. Roche is 2011 Supreme Court case addressing ownership of patent rights in inventions created pursuant to federal funding and subject to Bayh-Dole. The case was about control over rights in a test kit developed to detect HIV in human blood. As the Court explained the relevant facts:

Dr. Mark Holodniy joined Stanford as a research fellow . . . When he did so, he signed a Copyright and Patent Agreement (CPA) stating that he “agree[d] to assign” to Stanford his “right, title and interest in” inventions resulting from his employment at the University.

At Stanford Holodniy undertook to develop an improved method for quantifying HIV levels in patient blood samples, using [polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, a Nobel Prize-winning technique developed at Cetus]. Because Holodniy was largely unfamiliar with PCR, his supervisor arranged for him to conduct research at Cetus. As a condition of gaining access to Cetus, Holodniy signed a Visitor’s Confidentiality Agreement (VCA). That agreement stated that Holodniy “will assign and do[es] hereby assign” to Cetus his “right, title, and interest in each of the ideas, inventions and improvements” made “as a consequence of [his] access” to Cetus.

For the next nine months, Holodniy conducted research at Cetus.

The conflict was ultimately about whether Stanford could prevent Roche, the company that acquired Cetus’s IP assets, from using the invention.

At the Supreme Court, the court was asked to address the apparent conflict between 1) the ordinary rule in patent law that rights in an invention belong to the inventor and that “in most circumstances, an inventor must expressly grant his rights in an invention to his employer if the employer is to obtain those rights” and 2) the contention of Stanford University that Bayh-Dole changed this ordinary rule and instead gave it first priority in that invention, such that an individual inventor couldn’t just sign away rights to a third party.

Stanford made this argument about Bayh-Dole in part to protest against an important decision in the appellate court below; namely, that Stanford’s agreement with Dr. Holodniy was a “mere promise to assign rights in the future, not an immediate transfer of expectant interests” and therefore came second in line to Holodniy’s agreement with Cetus which allowed it to “immediately gained equitable title to Holodniy’s inventions.”

The Supreme Court concluded that Bayh-Dole did not disrupt the ordinary rule that inventors own rights in their inventions absent an express assignment, and because Holodniy’s agreement with Stanford used ineffective language to secure for it first priority—“agree to assign” instead of the effective “do hereby assign”—Stanford lost. The practical upshot—many of you may remember this—was that universities rushed to revise their agreements with employees to put in place more effective language securing first-priority rights in inventions of university employees.

Federal grants and copyright—what’s a university to do?

Stanford v. Roche contains some important lessons for universities, as federal grant recipients, about securing clear and effective rights from employees to comply with their grant obligations.

Like in Stanford v. Roche, in the context of copyrightable works created pursuant to federal funding, it’s also important for universities (as grantees) to make sure they actually hold sufficient rights in copyrightable works produced under that grant so they can comply with federal agencies’ public access requirements. That said, there are some important differences between the assignment of patent rights issues in Roche and what is required for compliance under the federal purpose license.

Probably the biggest determining factor in the effectiveness of those licenses will be how universities craft and implement their copyright policies. We’ve touched on this before, and explained that one important factor to consider is whether copyright law’s “work made for hire” doctrine applies (patent law has no such thing). Under copyright’s work made-for-hire doctrine, a work produced within the scope of employment is owned initially by the employer rather than an employee. Whether and how “work made for hire” applies to academic work is contested, but if it does apply, it largely eliminates concerns about priority of the university’s license since the university would be the initial owner. That’s true even though most universities (very rightly in our opinion!), make it clear that individual authors should ultimately be in control of rights in their works. For instance, the University of Michigan transfers the copyright of scholarly works to its faculty members, but reserves the ability to make uses consistent with academic norms, including complying with a Federal Purpose License.

Even without the application of work for hire, universities can and do use their copyright policies to effectively address ownership and licensing of faculty created scholarly works. Though we haven’t read every university’s copyright policy, for the most part we’ve found them to be thoughtful about securing from faculty authors at a minimum a non-exclusive license that would satisfy the requirements of Section 205(e) of the Copyright Act, giving it priority over any subsequent transfers such as a publishing agreement with a publisher. We review some of these approaches university policies take in this post, and we plan to release a white paper on this subject in the next few months. If you want to read further now, Law Professor Eric Priest has a good article, “Copyright and the Harvard Open Access Mandate,” that explains why these kinds of licenses are likely effective.

Conclusion

It’s important to remember that patent law and copyright law are distinct in many ways. While they share some similar concepts, the details are important and ownership and licensing of rights under one can be quite different from the other. The Bayh-Dole Act and other U.S. patent law govern ownership and commercialization of federally funded inventions, but they do not dictate how the Federal Purpose License should be interpreted or applied within the confines of copyright law.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.