The copyrightability of AI-generated works is a hotly debated issue. We recently blogged about the first US appellate court decision on the copyrightability of AI-generated works. In Part I of this blog post, we examine the five decisions handed down by Chinese courts so far on the copyrightability question over AI-generated works.

We believe ours is the first attempt to examine these five cases together. These copyrightability cases, individually, are receiving lots of attention in Chinese media. The general public in China has very pro-copyright and pro-enforcement sentiment nowadays. This may explain why courts have issued decisions that largely sided with the creators of AI-generated works; according to some judges in China, their job is to issue rulings that fit with the expectations of the plaintiff, the defendant, and the public.

These AI copyrightability cases are barely ever discussed together as congruent jurisprudence, because, like with most legal questions, courts in China rarely need to pay attention to precedents. Only since 2010 are courts in China required to follow certain Supreme People’s Court’s decisions. None of the cases discussed below are precedential.

These decisions, then, are just one-off incidents—barely impactful in terms of damages born by the defendants or precedential effects for future cases to be decided in China. The deadline for appeal has long passed for all five cases, and the decisions are final for the parties involved. But for people in the US, one big question is whether these Chinese courts’ non-precedential decisions could potentially be upheld and enforced by US courts. We consider this question in Part II, below.

Part I, Chinese Courts’ Copyrightability Holdings

China’s judicial system seems to be moving really fast. While most countries are still slowly working toward articulating their stance on AI-generated works, courts in China have already released multiple opinions addressing AI, both in terms of training and copyrightability of AI output. Researching these cases is challenging, however, because there is no single unified database for court opinions in China.

In Beijing Feilin Law v. Baidu, the Beijing IP Court issued an appellate decision in 2020 partially upholding and partially overturning the lower Beijing Internet Court’s 2019 decision. Many refer to this case as the first case in China dealing with computer-generated works, because part of the dispute was centered on whether some computer-generated charts were copyrightable. In reaching the decision that the computer-generated charts are not copyrightable, the appellate court reasoned:

Although there are differences in the graphics, shapes, and the data represented, these differences resulted from choices in data selection, software, or graphics. The graphics used are common shapes in data analysis like bar charts, pie charts, and line graphs, which do not reflect the originality of Feilin Law Firm’s expressions. While Feilin Law Firm claims to have manually enhanced the lines and colors of these graphics, no evidence has been provided to support this assertion.

The court still managed to award Feiling Law Firm damages based on the right of integrity, because when Baidu reposted Feilin’s article, Baidu deleted more than 20% of the article. The damages awarded was 1,000 rmb plus 560 rmb in reasonable fees (totaling about $216 USD—peanuts to Baidu, which is valued at $34.5 billion USD). Overall, because the court refused copyright to the computer-generated charts, we are tempted to infer that human authorship is necessary for a computer-generated work to be copyrightable in China, very similar to the rule in the US.

At first glance, a second case, Tencent v. Shanghai Yingxun, confirms the assumption that human authorship is necessary for copyright protection for AI-generated works in China. However, the ruling is not entirely straightforward once we examine more closely the court’s reasoning on what constitutes the original human authorship needed for copyright protection:

The article was created through (1) data training, (2) prompting and article generation, (3) AI-enabled editing and (4) AI-enabled publication. In this process, the Plaintiff’s team members had to make selection and determination on the cleaning and inputting of data, prompt engineering, the selection of article template and language corpus, and the training of the editor function. The key difference between the creative process in this case and what we commonly see with other human creative processes is that the original human choices are made prior to when the article was written in terms of what data to use, what theme to focus on, and what style and tone to adopt. This court holds that such asynchronicity is caused by the technology. … If we consider the two-minutes it took for the article to be generated to be the entire creative process, then no human authorship was involved; however, Plaintiff determined how the program was run, and the article was generated in a way that was determined by both how Plaintiff intended that program to work and how the program functions based on its technical characteristics. If we see the two-minutes it took to generate the article as the creative process, we are in effect taking the machine to be the author of the article, which does not match our understanding of reality or justice. … We do not need to investigate if the originality of the article stems from the contributions by the program’s developer, because the developer has already agreed in a contract that the Plaintiff holds copyright to anything created by the program.

This case resulted in 1,775 rmb (around $245 USD) fees and damages awarded against the Defendant; the impact is minimal on the parties directly involved. Even though the opinion affirmed the necessity of human authorship, the reasoning behind it is in direct opposition to the US Copyright Office’s position on the lack of copyrightability for AI-generated works. Whereas a consensus is forming in the US that AI outputs are beyond the controls of humans, that prompt engineering does not lead to foreseeable outputs, and that AI-generated works are categorically uncopyrightable, China seems to be leaning towards an unsustainable position that any human input at all during the prompting stage could lend copyright protection to an unpredictable AI output.

In late 2023, for the first time ever in the world, a court got to determine whether a user owns copyright to an entirely AI-generated image in the case of Li Yunkai v. Liu Yuanchun. The Plaintiff in this case was a lawyer by profession; he also created visual art using text-to-image generative AI on the side. The Beijing Internet Court reasoned:

As to whether images generated using artificial intelligence reflect the author’s individualized expressions, it requires case-by-case determination. Generally speaking, when people use models like Stable Diffusion to generate images, the more their requests differ from other users and the more specific and clear the descriptions for the image and composition, the more the author’s individualized expressions will be reflected in the final image. In this case, the image exhibits identifiable differences from prior works. On the one hand, the plaintiff did not personally draw the lines or even fully instruct the Stable Diffusion model on how to draw particular lines and colors, it can be said that the lines and colors that form the images were essentially “drawn” by the Stable Diffusion model, which is quite different from how people traditionally use brushes or drawing software. However, the plaintiff designed the female character and its presentation via prompts, and set the layout and composition by changing image parameters, reflecting the plaintiff’s choices and arrangements. On the other hand, after obtaining the first image by initially inputting prompt words and setting related parameters, the plaintiff continued to add prompt words and modify parameters, continually adjusting and correcting the image until the final image was achieved. This adjustment and correction process reflected the plaintiff’s aesthetic choices and personal judgment.

Essentially, the court granted copyright to AI output based on prompt engineering alone. The Defendant was ordered to pay the Plaintiff 500 rmb (around $69 USD) for removing the copyright notice as well as distributing the infringing image online without permission. The Plaintiff accepted the court’s holding, but refused to take any money from the Defendant, saying money was not what he was seeking. The decision is criticized by some Chinese scholars for granting copyright to wholly AI-generated images, potentially leading to an oversaturation of AI-generated images, further marginalizing human authors. There remain strong proponents in China that advocate for a bright line rule—that AI-generated images are never copyrightable.

With the previous two cases in mind, it should not come as a surprise that, in 2024, the Plaintiff in Lin Chen v. Hangzhou Gaosi Membrane Technology was able to assert his copyright in an AI-generated image when he used both Midjourney and Photoshop to manipulate the image. The court examined the contract terms between Midjourney and Plaintiff, as well as looked at the prompt-author’s activity log and creative process, before reaching the conclusion that the AI output was copyrightable. The court reasoned that the work was copyrightable because the Plaintiff had creative control over the output and the output embodied the author’s intended original expressions, and socially-speaking, allowing prompt-authors to be copyright holders to their AI output would encourage more creative activities that utilized AI. The key facts related to the creative process are as follows:

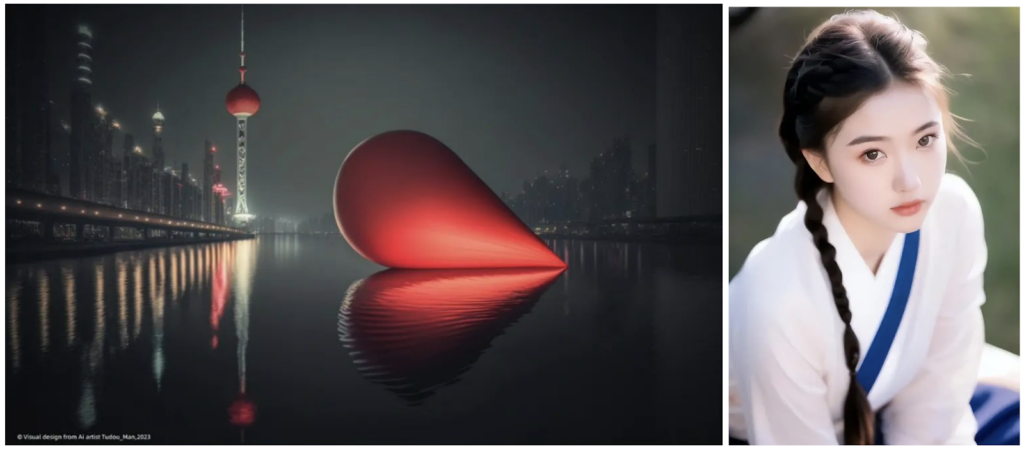

The plaintiff began designing the image using Midjourney GAI. Initially, Plaintiff entered the following prompts: “On the Huangpu River” “at night” “there is a string of large and small hearts” “floating in the water” “lights” “advanced” “reflection” “details” “ realistic” “4k ” “no people” “High environment/Canon E0S 5Diii” and Midjourney generated four images with heart-shaped balloon. The Plaintiff continued to engineer prompts, such as inputting “there are multiple red love balloons”“there is a huge red love balloon” “lying on the water” “half soaked in water” “rose petals composed of love” “only half of the surface of the water” to manipulate the size, number, shape, and position of the balloons. When the output was unsatisfactory, the Plaintiff took the image to Photoshop, changing the shape of the balloon, and reimported the resulting image back into Midjourney for further tweaking. After that, the Plaintiff took the image to Photoshop once again before finalizing the design on 2023/2/14 at 23:40.

In this case, beyond copyright infringement through unauthorized distribution, the removal of copyright notice was also found to be infringing on the Plaintiff’s right to integrity. The Defendant was ordered to pay 1,000 rmb in damages and 9,000rmb in reasonable fees (totalling around $1383 USD). Interestingly, the Defendant was only held liable for reposting the image, but not found infringing for creating a 3D submerged-heart statue based on the infringing 2D image. Some people—including the Plaintiff—argue that this result is only due to mistakes made in the copyright registration process, that the Plaintiff failed to register 3D rendition of his 2D design. Although, a more compelling reading of the opinion would be that copyright for a half-heart design is thin, and people are free to make different renditions based on the same half-submerged heart idea.

Similar to the reasoning provided in the Li Yunkai case, this February, the court in Wang v Wuhan Technology Company (The link takes you to the court’s official report; full opinion for this case could not be found as of 3/20/2025) determined that the Plaintiff’s AI-generated work was entitled to copyright protection because the Plaintiff could foresee and control the resulting image to a certain extent, and the prompts Plaintiff inputted into the AI system embodied his unique human expressions which directly correlated to the final AI-generated image. Defendant was ordered to pay 4,000 rmb (around $553 USD) for their infringement.

As we mentioned at the beginning, these cases are not precedential in China, despite being final. If the general societal sentiment in China continues to lean towards AI-artists receiving copyright protection for their works, any new rulings would likely come out similarly—granting copyright to AI-generated works. Until inevitably, the Chinese courts must re-examine their flawed reasoning, when stockpiling happens, when AI companies stop assigning “copyright” to users of their AI models, when human authors start to lose jobs en masse, and when the judges can’t figure out if an AI-artist should be held liable for a copyright-infringing AI-generated image when all the artist has done was providing some simple text-prompts.

Part II, Will US Courts Grant Copyright Protection to Foreign AI Works?

Looking beyond China, the UK, Ireland, South Africa and Ukraine all have adopted laws that specifically grant copyright to computer-generated works. In this part, we discuss whether copyright granted in foreign jurisdictions will be upheld by US courts.

There are two main questions US courts may need to consider regarding foreign AI-generated works: (1) whether to apply foreign law to determine the copyrightability of foreign AI-generated works, and (2) whether to enforce foreign judgments that upheld AI-generated work as copyrightable and unlicensed use infringing.

First, will US courts defer to foreign law when determining whether AI-generated work created in a foreign jurisdiction is copyrightable? We think it unlikely.

The issue raises what is known as a “choice of law” question. The answer in the copyright context depends on how US law incorporates obligations under international treaties such as the Berne Convention, as well as common law principles that are more generally applicable. Itar-Tass Russian News Agency v. Russian Kurier, Inc. (2d Cir. 1998) is among the most cited cases to decide this issue under the current Copyright Act. In Itar-Tass, when deciding whether to apply US law or foreign law, the court distinguished between the question of copyright ownership and the question of copyright infringement. For copyright ownership of a foreign work, the Second Circuit applied foreign law.

For infringement issues, Itar-Tass states that “the governing conflicts principle is usually lex loci delicti. . . . We have implicitly adopted that approach to infringement claims, applying United States copyright law to a work that was unprotected in its country of origin.” (citing to Hasbro Bradley, Inc. v. Sparkle Toys, Inc., (2d Cir.1985). The distinction between ownership and infringement is not arbitrary. The infringement question addresses the scope of copyright protection, whereas the ownership question addresses who gets to enjoy that protection. It is well established that the US does not grant additional protection to foreign works compared to US works: for example, in the US, a foreign copyright holder would not be able to point to foreign laws to request moral rights for his work (see Fahmy v. Jay-Z (9th Cir. 2018)).

Because the United States has joined the Berne Convention and implemented it in US Copyright Law, U.S. courts must give the same protection to foreign works as to US works, and this deference to foreign copyright includes a presumption of the foreign copyrights’ validity. However, the presumption of validity is different from a copyright being in fact valid under US copyright law: a defendant can always challenge a registered, presumptively valid, copyright. As discussed in Unicolors, Inc. v. H&M Hennes & Mauritz, L.P. (9th Cir. 2022), “[equal treatment] simply means that foreign copyright holders are subject to the same U.S. copyright law analysis as domestic copyright holders… [I]t does not mean we can change the rules of the game simply because foreign copyright law is implicated.” Whether an AI-generated work is copyrightable similarly would have to be equally subject to review under US copyright law, regardless of whether it was created in the US or a foreign jurisdiction.

Many cases have followed this principle that US law will be applied when determining questions of originality and copyrightability. In Molnarova v. Swamp Witches (S.D. OH 2023), a case brought by Slovakian artists, the district court explained “Although [Plaintiff] is correct in asserting that Slovakia law applies to the question whether she owns a copyright in the Tumblerone, the question of who owns a copyright is distinct from what protection that copyright provides. The latter is governed by United States law, more specifically the Copyright Act. In other words, even if Slovakia offers copyright protections to the Tumblerone as alleged by Plaintiff, she must still show that the Tumblerone is protectable under United States copyright law.” (citing to a series of other cases in agreement.)

One notable outlier to this rule is TeamLab v. Museum of Dream Space (C.D. CA 2023), where the court applied Japanese law in deciding whether the works in question were copyrightable. The TeamLab court essentially only required valid copyrights in Japan for the works to automatically enjoy copyright protection in the US. Because the works were “creatively produced expressions” eligible for copyright in Japan, the court accepted the works as protected by valid copyrights in the US as well, without explicitly scrutinizing the works under US law. The Teamlab court’s confusion likely arose out of the court’s conviction that applying US law would have led it to the same conclusion (—e.g., with language like “in both Japanese and U.S. copyright law, a work need not be novel to be original” and “Under both Japanese and U.S. law, Plaintiff retains a copyright”).

Even if a court were to follow Teamlab and apply foreign law on the question of copyrightability, a US court may still very likely interpret Chinese law to grant no copyright to AI-generated works. On paper at least, China only grants copyright to “fruits of intelligence” (Art. III, Copyright Act) which so far has been interpreted to mean human intelligence and human authorship. Especially when so many Chinese legal scholars do not believe AI-generated works contain enough “human intelligence” to warrant copyright, it is likely a US court will determine AI-generated works are uncopyrightable under Chinese copyright law. In any case, defendants in US courts would almost always want to challenge the validity of copyrights given to AI-generated works.

Let’s now move on to the second question: Will plaintiffs be able to enforce foreign copyright judgments in the US? We believe there’s a possibility that opinions issued by foreign courts granting AI-generated works copyright protection will be enforceable in the US, but jurisprudence seems unsettled in this area.

We have written about one case addressing this issue before: when the Plaintiff in Sicre de Fontbrune v. Wofsy (9th Cir. 2016) sought to enforce a foreign judgment on copyright infringement, the Ninth Circuit did not second guess the French court’s decision on copyrightability, even though the work at issue was a faithful 2D scan of an existing work, lacking originality and thus uncopyrightable under US law. The defendant did not request the Ninth Circuit to reexamine the copyrightability issue. Had the defendant raised the argument that the photograph in question did not meet the originality requirement under French law—or under US law, maybe the Ninth Circuit would have done its own copyrightability analysis. We cannot be sure how the case would have played out had the question been raised.

In a similar case brought to the Second Circuit, SARL Louis Feraud Int’l v. Viewfinder (2nd Cir. 2007), the circuit court explained that courts rarely refuse to enforce foreign judgments unless they are “inherently vicious, wicked or immoral, and shocking to the prevailing moral sense.” The circuit court reasoned that “if the sole reason that Viewfinder’s conduct would be permitted under United States copyright law is that plaintiffs’ dress designs are not copyrightable in the United States, the French Judgment would not appear to be repugnant. However, without further development of the record, we cannot reach any conclusions as to whether Viewfinder’s conduct would fall within the protection of the fair use doctrine.”

Essentially, the circuit court made the distinction between copyright protection (which is an economic right fabricated by Congress that does not implicate morality or public policy) and fair use, which is an embodiment of a First Amendment right that represents strong public policy concerns. When SARL was remanded to the district court, the French judgment was not enforced. In reaching its decision to not enforce the foreign judgment, the district court did not address the copyrightability issue (that fashion design is uncopyrightable in the US), but entirely based its decision on a fair use analysis rooted in US copyright law, in accordance with the circuit court’s instructions.

Notably, the circuit court in SARL referred to the relevant state statute, N.Y. C.P.L.R. § 5304(b)(4) (and New York’s adoption of the Uniform Foreign-Country Money Judgments Recognition Act) as the basis for its decision. There is no federal law regulating the enforcement of foreign judgments, and the US is not a party to any international treaty that requires US courts to enforce foreign judgments. (Compare the situation to how the Berne Convention obligates US courts to provide copyright protection to foreign works.) Most states have similar laws about enforcement of foreign monetary judgements, though there are some important differences. Depending on the applicable state laws, US courts can sometimes substantively review foreign judgments, like when the SARL court relied on fair use under US law. A defendant should have a fair use defense ready if a US court is considering enforcing a foreign copyright infringement ruling.

Even if courts were to enforce the opinions issued by Chinese courts, the good news is that Chinese courts typically award limited damages to the plaintiffs (because AI works are cheap to generate). Also important to remember is that foreign courts only address infringing acts in their jurisdictions, so this is not an issue for parties without an overseas presence. US courts also take procedural due process into account when deciding whether to enforce a foreign judgment; it would be farfetched to worry that US courts will enforce foreign judgments entered against entirely unsuspecting US defendants.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.