Bonds, Beats, and Lawsuits: How Ed Sheeran Won

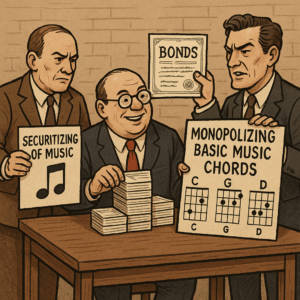

Structured Asset doesn’t make music nor aim to enrich our cultural life; instead, it uses copyright enforcement as a weapon against artists like Ed Sheeran, and turns a system meant to protect creativity into a mere vehicle for chasing profit.