James J. O’Donnell is the University Librarian at Arizona State University Libraries and has published widely on the history and culture of the late antique Mediterranean world. He successfully reverted rights to his 1992 edition of Augustine’s Confessions and made the book available in an open access digital version. Continued interest in the online book led to a subsequent reprint and later an additional paperback print run. Professor O’Donnell shared his rights reversion experience with us in the following Q&A.

Authors Alliance: How did you first learn of rights reversion?

James O’Donnell: In the course of becoming involved in digital publishing in 1990 and after (and founding the oldest open access online journal in the humanities, Bryn Mawr Classical Review), I had been around conversations about rights and about signing away as little as you need to [in a contract]. The book in question, Augustine: Confessions (Oxford University Press 1992, 3 volumes) was in my mind at the time, so I familiarized myself [with rights reversion].

My book was expensive and specialized, with a first print run of 1,000 copies and a provision that I would get royalties if it sold more than 600 copies. The book sold for $300, or about $550 in 2018 dollars. I figured this meant that OUP expected to sell 600 copies, or a few more. In fact it had a reprinting of 250 copies and sold out all of those. In 1995, my editor at Oxford told me with regret that she had been unsuccessful in getting a paperback edition, so the book was going out of print. I was remarkably cheerful about this prospect [because it made the book eligible for reversion].

AuAll: What motivated you to request your rights back?

JJO: I had been speaking of digital “postprints” for some time and had in fact posted an earlier book of mine from 1979 (long out of print) in that way. The Oxford volumes of Augustine’s Confessions were meant to be of high value for scholarly users, from student to researcher, and I was well aware that use was naturally limited to library copies, often non-circulating. I wanted better.

AuAll: Were you eligible to exercise a clause in your contract granting reversion rights?

JJO: Yes, I wrote a simple letter to Oxford University Press. There was a clear clause in the contract.

AuAll: How has the reversion helped you? What have you been able to do with your book since reversion?

JJO: First, I worked with a consortium of scholars doing Internet publishing in classics to create a digital online version of my edition of Augustine’s Confessions, now hosted at the Stoa Consortium and at Georgetown University (my former institution) on mirror sites. This resource has been available for about twenty years and is regularly praised as a teaching and research tool of considerable value.

Then, in about 2000, OUP decided to have another publisher, Sandpiper Books, do limited run reprints (not yet print-on-demand) of some of their “greatest hits” of scholarly publishing in classics, and chose to include Confessions in the series. When they told me they intended to do this, I reminded them that the rights were now mine, and we proceeded to agree on terms for licensing this specific use for a modest stipend.

Around 2012, OUP decided that the book indeed had legs and made it available in paperback. It has been in print in that format since 2013 for $179, or about one-third the original hardcover price. It was surely the case that the digital presence with open access on the web kept my book in mind and created the market for those who decided they needed a print copy. It is highly unlikely that the book would have had better sales without the e-version (and quite likely that it would not have done as well).

AuAll: What advice do you have for other authors who might want to pursue a reversion of rights?

JJO: Authors should know what they want out of their books, other than the traditional thin stream of royalties that academic books receive. They should inform themselves about their rights, sign rights away carefully at the outset, and then keep an eye on just what outcome they are looking for. My sense is that with the ease of print-on-demand technology, many books may effectively never go “out of print,” requiring a different kind of strategy and vigilance for authors.

__________________________________________________________________

We couldn’t agree more! Authors should be informed about their rights, and have strategies in mind for using them wisely—not only at the time a book deal is signed, but in future years, as well. To that end, we recommend two of our educational resources to help authors understand what exactly rights reversion is, how reversion fits into a book publication contract, and how to successfully secure a reversion of rights.

If, like Professor O’Donnell, you have previously published books and wish to learn more about regaining your rights, visit our Rights Reversion resource page, where you’ll find our complete guide to Understanding Rights Reversion, letter templates for use in contacting your publisher, and a collection of reversion success stories from other authors who successfully regained their rights and made their works more widely available.

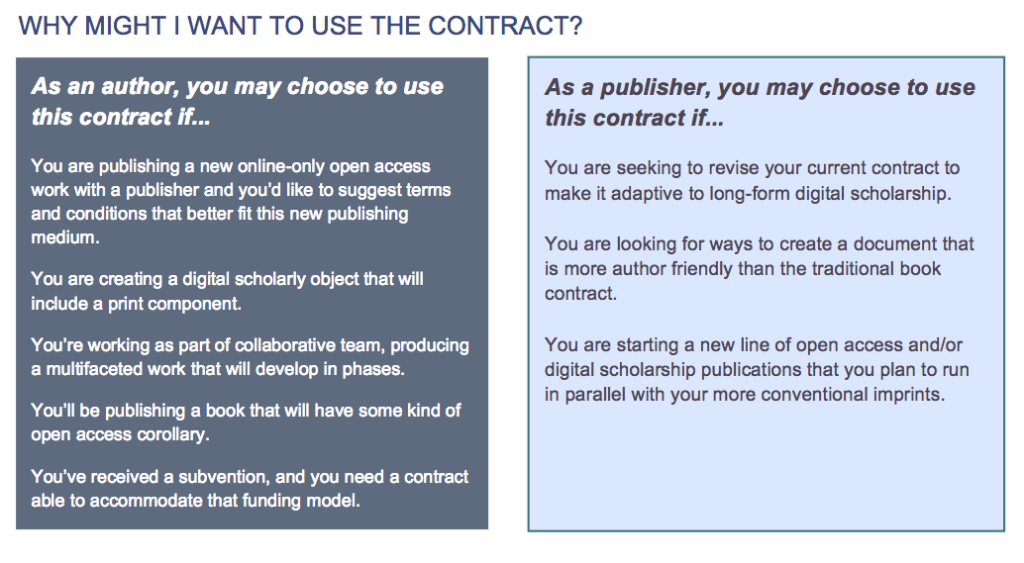

If you currently have a book in progress and have not yet placed it with a publisher, we also recommend visiting our Publication Contracts resource page, which features our new guide to Understanding and Negotiating Book Publication Contracts. Knowing about rights reversion and reversion clauses before you sign your publication contract can help to clarify the conditions for reversion and pave the way for a successful reversion of rights in the future.

This summer, Authors Alliance founding members

This summer, Authors Alliance founding members